A shadow director is a person or company that has significant influence over a company’s affairs without being formally appointed as a director. This is sometimes so they can have control over a company without their name being associated with it and/or so they can avoid the liabilities that go with being a company director.

The legal definition of a shadow director is broad and can include both individuals who intentionally act as shadow directors and those who may unwittingly become one due to their influence and control over the company. Here we suggest some steps to avoid being involuntarily labelled as a shadow director when acting in an advisory capacity.

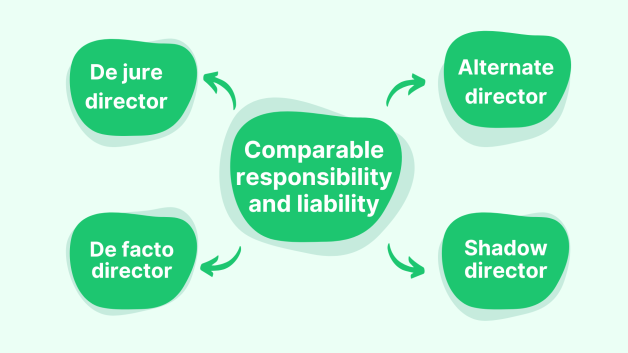

To begin with, a few quick definitions of types of company director may help.

Manage company officers and PSCs

Like everything else to do with your companies' filing requirements, Inform Direct handles company officer and PSC filings with ease and simplicity, making sure you file on time and accurately.

Types of company director

For the purposes of this article there are four types of director:

- De jure. A formally appointed company director, registered at Companies House either at incorporation or later via form AP01 for an individual or AP02 for a corporate director. This includes non-executive directors (NEDs), who are formally appointed but act in an advisory or guiding capacity

- De facto. A person who is known as a director of the company and holds himself out as such but has not been formally appointed

- Alternate. A replacement who stands in for a de jure director in their absence. Alternate directors are treated exactly the same as the appointed director they are temporarily replacing

- Shadow. A person or entity that makes no claim to be a director but (arguably) is, by virtue of the degree of influence they have over the company’s affairs.

The law says that a shadow director is ‘A person in accordance with whose directions or instructions the directors of the company are accustomed to act.’

Shadow directors and the law

Shadow directors are subject to many of the same legal responsibilities as de jure directors, including the duties to act in the best interests of the company and its shareholders, to exercise reasonable care, skill, and diligence, and to avoid conflicts of interest. If a shadow director breaches any of these duties, they may be held liable for any losses or damage caused to the company.

The statutory concept of a shadow director is defined in the 1985 and 2006 Companies Acts as: ‘A person in accordance with whose directions or instructions the directors of the company are accustomed to act.’ Shadow directors can control a company in many ways, including where they have a chequered past or wish to remain anonymous and appoint a family member or close associate in their place as de jure director. They can thus avoid being publicly associated with the company while in fact pulling the strings.

The shadow director may do this by controlling the shareholders or executives of the company, or by giving instructions to the appointed directors outside of official meetings.

Advisers becoming shadow directors

The Companies Acts also provide that somebody is not a shadow director if the company acts on advice they give in a professional capacity as an external consultant.

This can be a contentious area because of the lack of a clear cut-off point between advising and directing. The concept of shadow director is designed to catch out those who want to exercise director-level influence over a company’s affairs without wishing to shoulder a director’s responsibilities. Advisers such as management consultants and advisory board members need to be careful to avoid slipping into too much of a directorial role – even in good faith – if they do not want the responsibilities and liabilities that go with it.

When are shadow directors identified?

Shadow directors are often identified after things have gone wrong at the company and accountability is being sought. If a court finds them to be a shadow director, a person or entity will be treated as if they were de jure. The main question will be the extent to which the person or company had real influence in the corporate affairs of the company. If it is found that their influence was regularly acted upon by the board, they will most likely be found to be a shadow director.

A shadow director may be liable if claims are brought against the directors of the company for breach of their directorial duties and/or for committing corporate offences. Among these is wrongful trading, a breach of a director’s duties by failure to act in the interests of the company’s creditors. This is a statutory offence under the Insolvency Act 1986. If this is proven the shadow director can be pursued for the company’s lost assets after liquidation.

Avoiding the ‘trap’

Courts tend to view shadow directorships as scenarios where the majority of a company’s board are accustomed to acting on a person’s advice over an extended period of time. The key word here is ‘accustomed’. There may be a period during which directors are acting on an adviser’s instructions but have not yet become used to doing so. When eventually seeking the person’s advice becomes a default option for the board of directors, that person will have morphed into a shadow director. Thus in the eyes of company law there is a cumulative aspect to becoming a shadow director; it happens over time.

While many companies regularly act on the guidance of professional advisers such as lawyers, there is usually no suggestion that those advisers are shadow directors. But when companies get into trouble and blame is being sought, there may be retrospective scrutiny of their roles and degree of influence on the company. Professional advisers should always bear in mind the possibility of such a scenario developing when dispensing their counsel.

Practical steps toward self-protection include:

- Having in place a service agreement, contract or letter of engagement that clearly defines the extent of their involvement with the company. It should focus on specific services to defined areas of the company and state explicitly that the adviser is not to be treated as a director.

- Avoiding board meetings where possible. When one must attend it is a good idea to have it recorded in the minutes that they were ‘in attendance’ rather than ‘present’. The convention is that directors and the company secretary are ‘present’ and all others are ‘in attendance’.

- Making it clear to all other parties that they are not directors of the company and are acting in their professional advisory capacity only.

- Ensuring that the company does not portray them as a director by using the title in written communications.

- Letting the board of directors make the major decisions. Everyone’s actions will be examined in the event of insolvency. A person’s status and therefore liability will be decided based on the regularity and decisiveness with which they wielded authority in the company.

- Avoiding getting involved in the company’s finance, participating in negotiations, and doing other things normally associated with appointed company directors.

- If in doubt, getting legal advice.

Any company that thinks an adviser is walking the line between adviser and shadow director should consider formally appointing them as a de jure director, . If it is not clear quite what they would be directing then it might make sense to appoint them as a corporate ‘minister without portfolio’: a non-executive director (NED). If they consent to this they can then advise, guide and influence to their heart’s content.

An important exception

The law says that a holding company should not be seen as a shadow director of any of its subsidiaries. For example, the CEO of a group of companies exerts influence over the boards of subsidiary companies of which he is not a director. This is explicitly permitted in the Companies Act 2006, 251: ‘A body corporate is not to be treated as a shadow director of any of its subsidiary companies by reason only that the directors of the subsidiary are accustomed to act in accordance with its directions or instructions.’

Keep your officer records and other company documents up to date with Inform Direct, a vastly improved interface with Companies House.